Three Weeks Solo Bikepacking Across the Alps

After graduating from Berkeley, I had an abundance of both free time and restlessness. Though I had never bikepacked before, nor ridden a bike in the past year, I decided that, before starting my Master's, I would spend 3 weeks biking solo across the Alps.

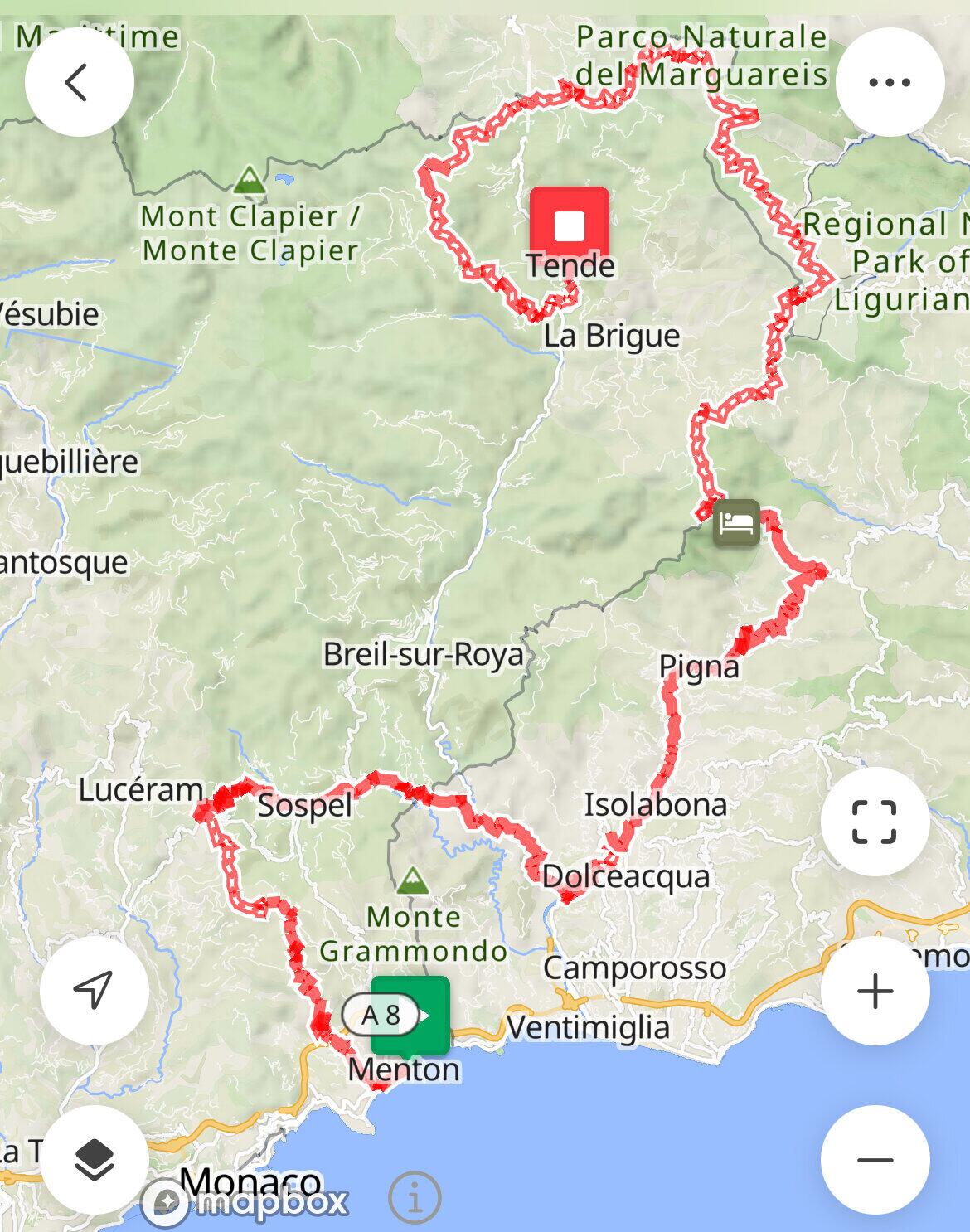

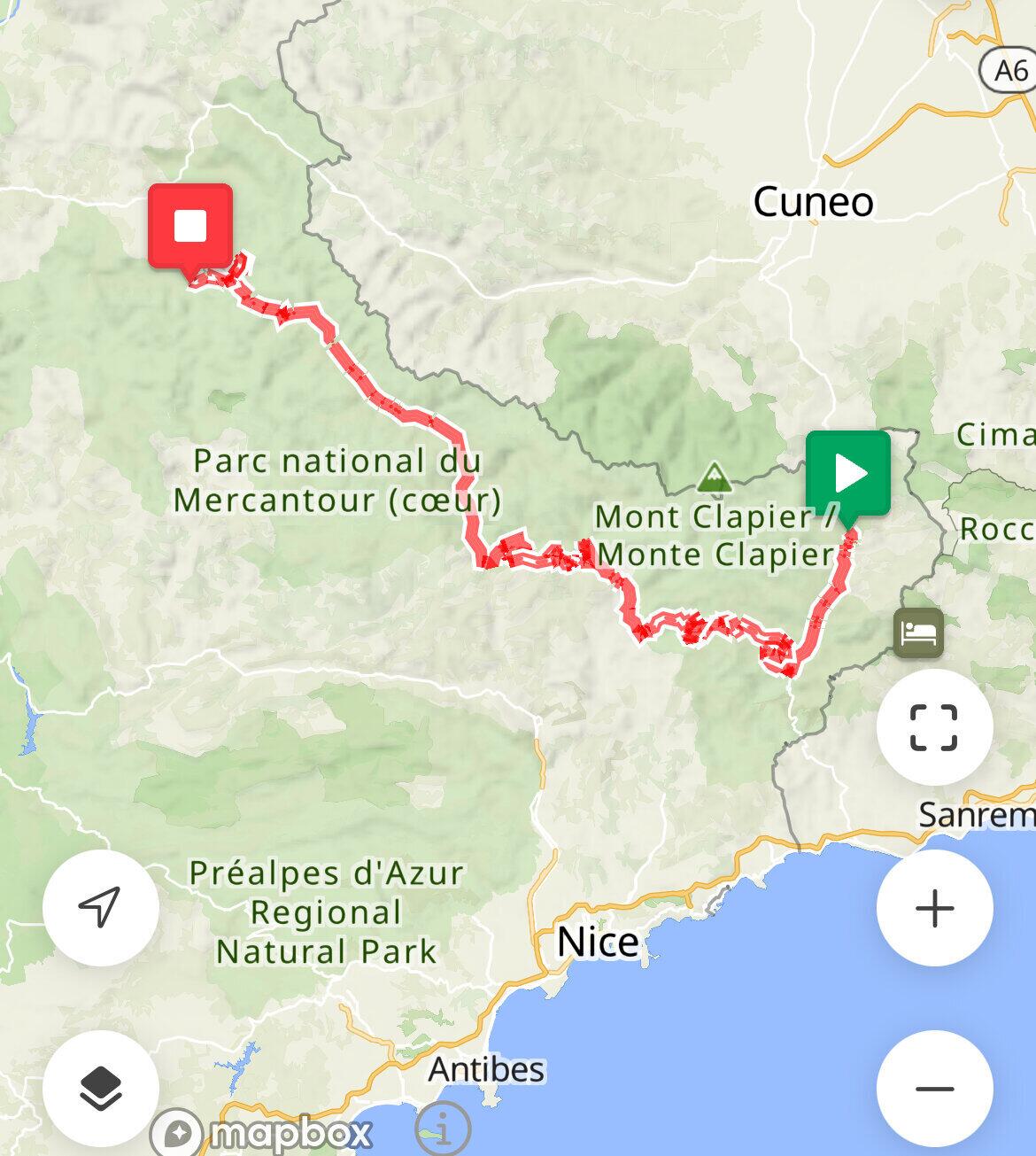

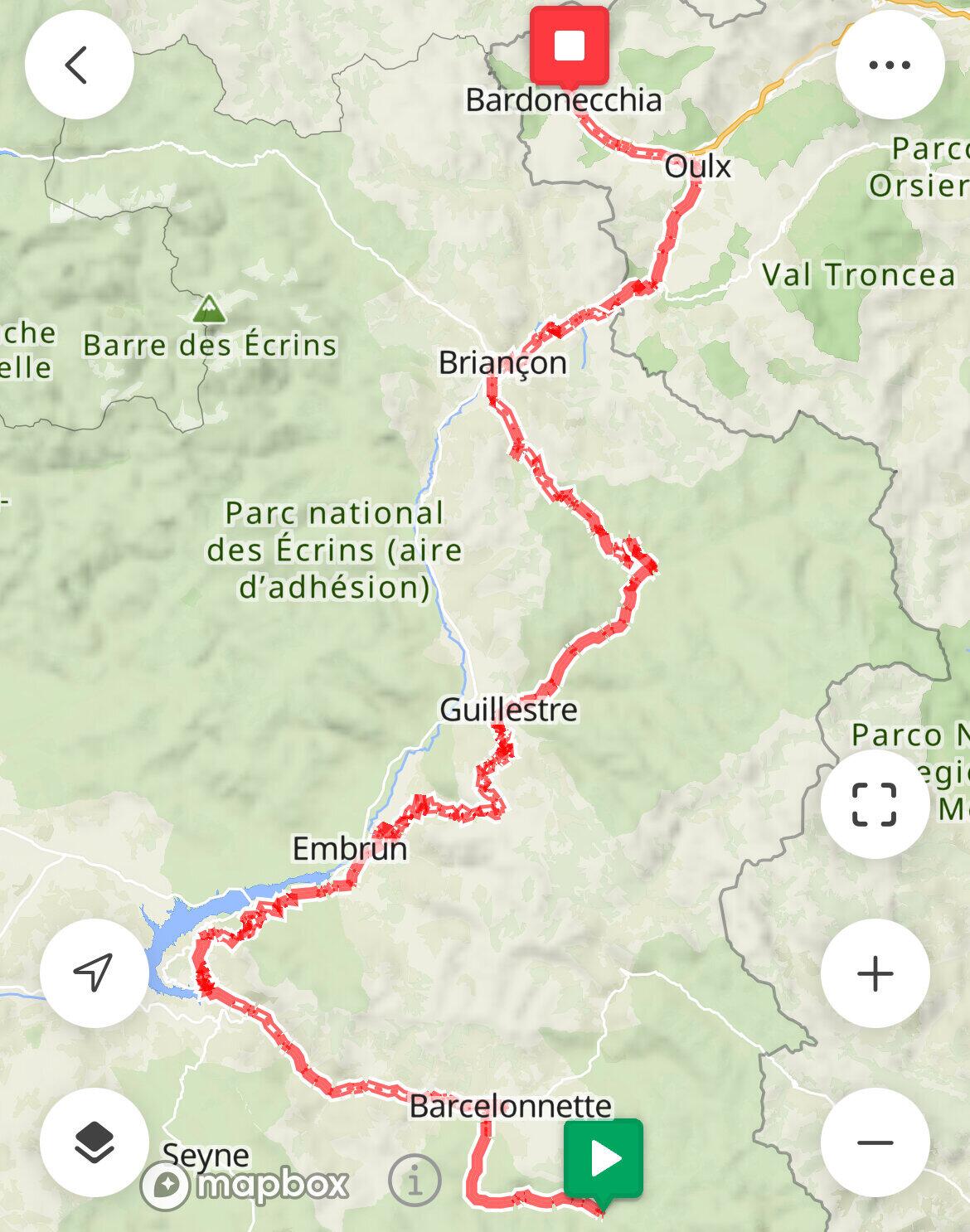

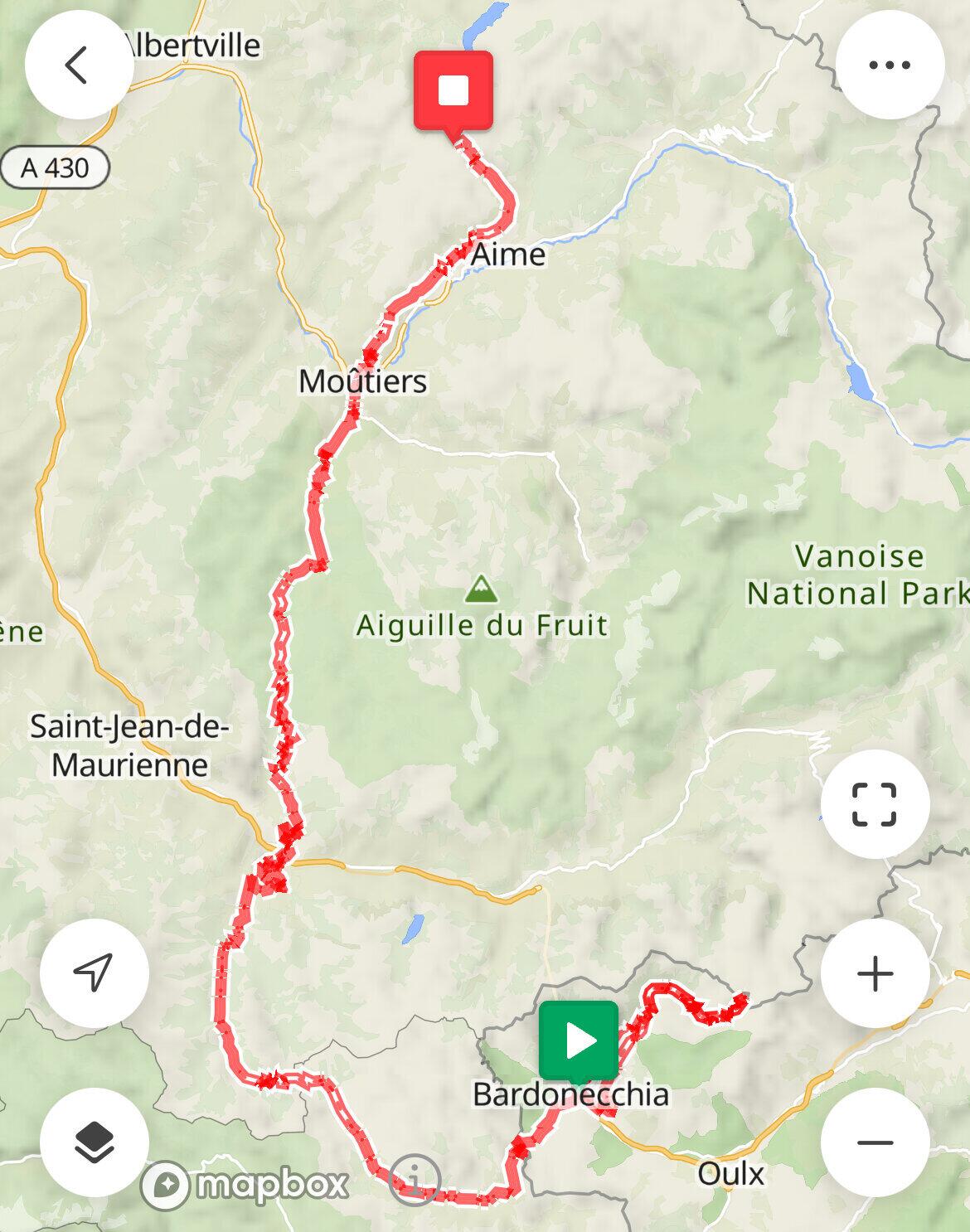

Generally following the route of the Alps Divide (not to be confused with the Route des Grandes Alpes), I ended up riding close to 850km and climbing 24,000m, of which around half was unpaved. The maximum temperature was around 38C and the minimum 4C, although this is largely a guess considering I had no connection on the coldest night. The maximum grade was 40... clearly some hike-a-bike involved. The bike's total weight fluctuated heavily with food and water requirements across segments, but 22-25 kg sounds like an appropriate general estimate. In hindsight, a more minimalist setup might've been beneficial. Now that we have the technical details out of the way, below is (the largely pictorial) story of what was partly a long bike ride, partly a lesson on the human experience, and a full assault on my GI tract.

Planning and preparation (or the lack thereof)

From ideation to realization, there was just over a month, and unless you've already been bikepacking, possess the necessary equipment, or are in excellent shape, this is less than ideal. None of these were true for me... and it showed.

I generally purchased the cheapest equipment possible, and salvaged my Dad's sleeping bag from the '80s, which I was unsure would be in solid enough shape to keep me warm. In the picture above, you can see my bag setup. I had a handlebar bag containing clothes and toiletries, a frame bag housing electronics and tools, a seat bag with food and water, and a dry bag strapped to a rear rack and the seat bag that held my sleeping bag, tent, and some thermal layers. I was quite happy with this setup at the start, but after just the first day, the handlebar bag and rear dry bag slipped frequently--forcing me to constantly readjust the bags and repair any tears with nylon tape.

The setup is not so unusual with the exception of the additional rear bag; most people opt for panniers if they need additional space. I thought I had discovered a nice little hack that kept my bike streamlined, but placing so much mass high-up in the rear makes it easy to fishtail on fast, loose turns while descending. I had two nasty falls as a result, and ended up scraped from my palms all the way down to my thighs. I frequently ignored or was otherwise unaware of conventional wisdom, and frequently, I paid for it.

With regards to physical preparation, I was running 40-50km per week across 3-4 days and biking a light 2-3 hours across 1-2 days. This isn't a lot, but then again, the goal was to prepare to survive in one month, not win the Tour de France. Why prepare by running for a bike trip you might ask? I figured that running would give me a chance to build up my aerobic base faster, and considering that I only had a month to get ready, it seemed reasonable to me. It worked (kind of). My aerobic base built up quickly, even if not quite as much as I would've liked, but I underestimated the importance of the bike-specific muscular adaptation required for long climbs. These legs were a-burnin'. Had I had more time to prepare, I would've spent at least one long day in the saddle a week.

For navigation, I used Ride with GPS on my phone, but on the Alps Divide, a good rule of thumb when at a fork in the road is to just pick the steepest ascent possible :). This rule isn't without its exceptions, however, and since I never bought a handlebar mount to easily check directions, I frequently found myself retracing my steps--a rather sad situation to find yourself in when you've spent 30 minutes descending the wrong way.

It Begins

After flying to Zürich and dropping my stuff off at my new apartment, I took the train to Ventimiglia, a small town in Italy on the border with France, before riding into Menton (pictured above) to the start of the official Alps Divide route. The climb starts almost immediately, and can be rather humbling if you don't already know what to expect.

Though the start of the trip was scorching hot, I found myself having to ride in cold weather gear just two days later. I ran into some farmers (not pictured) at a little dairy farm. My suspension broke.

I'm not a morning person, so I often started riding late and would have to rush to find a place to sleep at night. On the plus side, I was regularly still riding during sunset, and was rewarded with some amazing views.

The section of the military road picture above was one of the only parts with a guardrail. The descent felt sketchy. I met an older cyclist going in the opposite direction to me. We stopped to chat, and I asked him where he was headed. He proceeded to pull out a set of paper maps that were 1m x 0.5m before pointing out his route--just a reminder of the days before Google Maps.

The second ~250km

The frequency with which I saw cows was ridiculous. Even when they weren't visible, you could often hear their bells in the distance from another mountain.

I'm writing this several months after the fact, so it's difficult for me to recall some of the more minute details of the trip. That being said, I recall this day being pretty horrendous: a long, steep climb with pretty meh views, frequent cars or dirt bikes, swarms of flies following me, light but persistent rain, down to the last of my peanut butter and honey, and no place to poop.

The third ~250km

There was a long section before the lake pictured below where I was going in and out of these tunnels, but the headlamp that I brought to setup the tent at night was not great for visibility here.

The fourth ~250km

I only ended up doing around 100km of the 250 I had planned though; I decided to stop in Chamonix and meet up with a friend.

This is another one of those memorable days, but the lake and the views on the way here paid their dividends. Even though I would check the map for the climbs and unpaved sections before heading out for the day, it was often difficult to tell how hard a day would be ahead of time; it wasn't clear whether unpaved meant "gucci-gravel", large chunky rock, or hiking path that no sane person would try to ride with a fully-loaded bike. On this day, it was the latter; I was frequently having to pick up the bike or push it over a rock while I struggled to find a solid foothold. I remember averaging around 1km per hour for several hours.

In past years, it had snowed on the Alps Divide in July/August, which I was really looking forward to seeing. Unfortunately, this is about as close as I got to snow on the trip. There were prettier views of truly snow-capped mountains, but alas, my phone camera could only capture so much from a distance.

Since I've spoken relatively little about my diet, I figured I'd take the opportunity to do so now, and in the process, address this fantastic picture from my camera roll. My main source of sustenance on the trip was peanut butter with honey; pizza, dates, and salami get honorable mentions. My breakfast, at least at the beginning of the trip, consisted of muesli mixed with instant coffee, protein powder, and peanut butter, and throughout the day, I would usually snack on bread, peanut butter, honey, dates, salami, and chocolate. I would always try to find pizza or ice cream at some point in the day to up the calories, but just in case I failed to do so, I always kept a large can or two of tuna in olive oil, some red lentils, a bit of bulgur wheat, and bouillon cubes in my seat bag. I would then cook this over a "Super Cat" stove that I made from a can of FancyFeast (If you don't know what these--the Super Cat stoves--are, you should look it up; they're super cool.).

After a great deal of repetition though and realizing that my muesli breakfast wasn't filling enough, I discovered the breakfast of champions (an entire baguette, 200g of lox, and 750ml of milk... lactose intolerance who?), which I would treat myself to whenever I was sleeping close enough to a grocery store.

My first time hitchhiking! I ran across a farmer who let me load my bike into his truck and take a ride with him and his dog up the hill; it was only around 5 minutes, but I think he could tell I needed the break.

The owners of a refuge let me camp on their land for the night and cooked me dinner. For once, I had the descent in the morning instead of the climb. :)) The next day, a cyclist drove by in his van and offered me another short ride as well. His toddler, who was wearing a cycle cap btw, sat on my lap in the front seat, and we exchanged Stravas (the dad and I that is.. not the toddler).

Mont-Blanc was beautiful, and Chamonix is lovely. Unfortunately, I don't have any good pictures.

Final Comments

It's difficult to provide thoughts or reflections on such a trip without feeling as though I'm trivializing the experience, reducing it to clichés, or otherwise just being melodramatic. The truth is that I feel incredibly grateful to have been able to do it. To somewhat spontaneously find yourself biking solo through a place you've never seen before, where almost nobody speaks your language, and where you wake up with a singular goal--to keep moving--is something that not many experience.

You meet people you never would otherwise: farmers, herders, townspeople, and a million different flavors of vagabonds like yourself. You see places that most never will. You become accustomed to being the strange traveller in every town you enter, and to solving whatever problem the day throws at you with nothing but yourself and occasionally the kindness of strangers.

Truth be told, I was a bit disappointed in myself at the time for stopping in Chamonix instead of making it all the way to Lake Geneva, but my untrained body was reaching its limit, and the trip was never about the mileage or GPX files. It was about experiencing the freedom and power that comes with feeling the world in this way and with knowing you are capable. If I were to do it again, I'd probably prepare more in the interest of suffering a little less, but sometimes, there's nothing like jumping in the deep end.